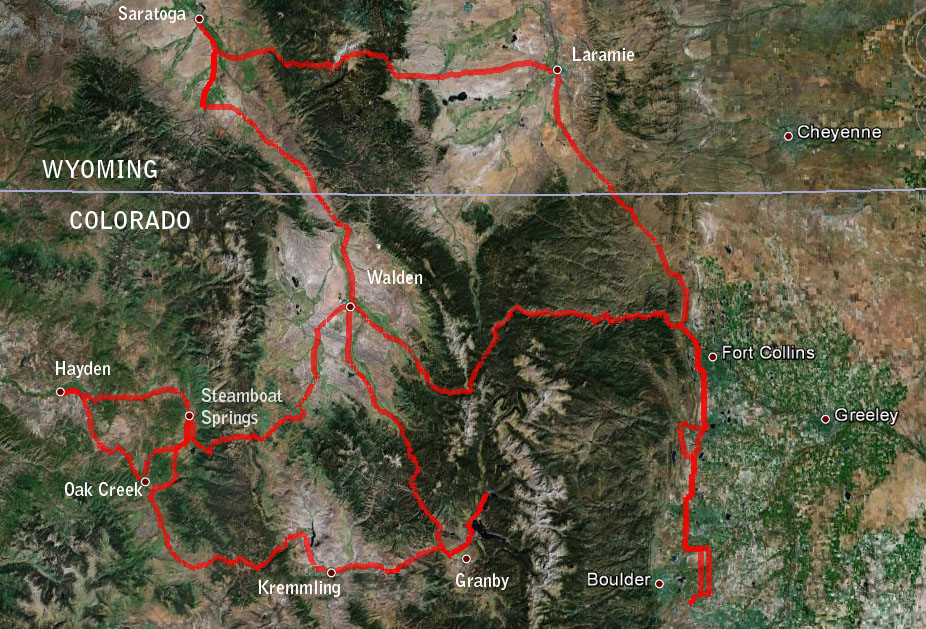

On July 9th - 12th, 2012, the Rocky Mountain Cycling Club (RMCC) organized and hosted a 1200 kilometer bicycle ride through the mountains of northern Colorado and southern Wyoming. Rides like this are held all over the world under rules sanctioned by Randonneurs Mondiaux and Audax Club Parisien. More information on this ride can be found at the Colorado High Country 1200 official website.

The ride is a timed event but not a race. All participants get the same award for finishing within the time limit of 90 hours. The 90 hours includes riding, eating, sleeping, bike repairs, everything. There were a few places along the route called "manned controls" where RMCC provided food, supplies, and places to rest but elsewhere the riders are left to their own devices. No personal support is allowed between the controls. You can beg, borrow, or buy supplies along the way as long as it's available to all riders. You have to ride the entire course as defined in the cue sheet, no shortcuts or alternate routes allowed unless you get specific permission from the organizer under special circumstances.

42 riders started from Louisville, CO on the 9th and 38 finished within the time limit on the 12th. I was one of the last group of 4 finishers, traditionally known as the "Lantern Rouge" group after the lights that were once used to mark the tail end of trains in France. I found this to be a difficult ride for various reasons but I enjoyed it immensely, especially the last day riding with friends new and old at the "back of the train".

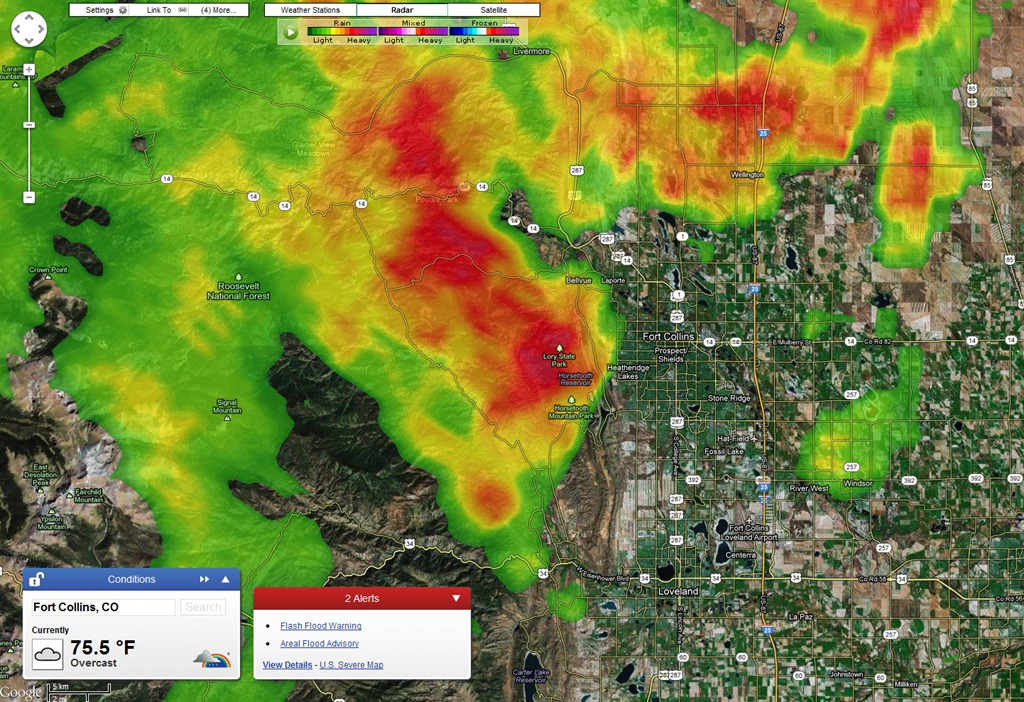

For the organizer, the difficulty of the ride began before we started. John Lee Ellis, president of RMCC, faced an enormous challenge finding a safe route due to the exceptionally bad fire season in 2012. He was constrained by the fact that the overnight stops were set and could not be changed and that the total distance had to come out to 1200k (or slightly more). There were several reroutes in the last week before the ride started.

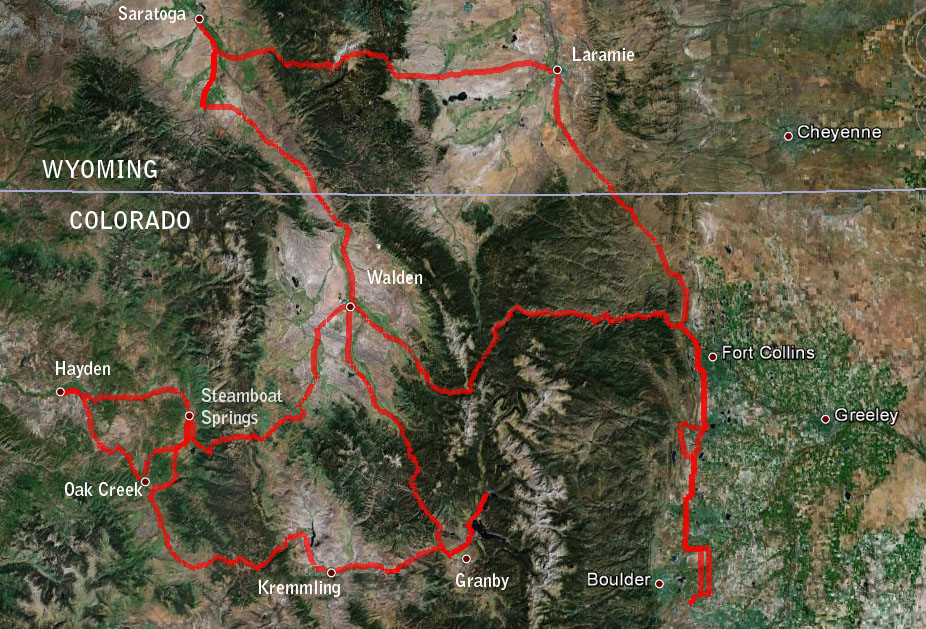

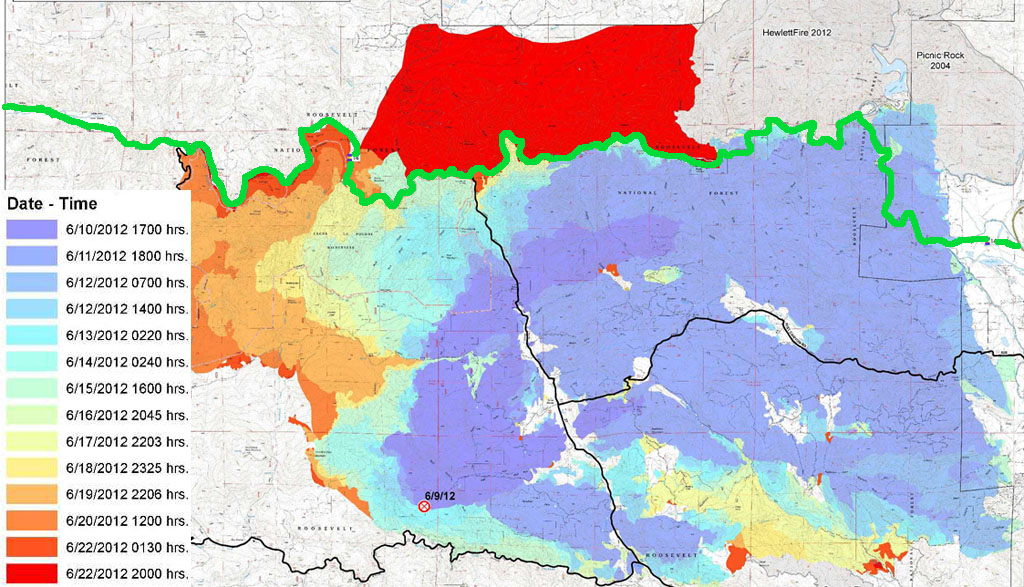

On June 9th lightning started a fire in the mountains above Fort Collins. Within 2 days it covered 36000 acres up to the Poudre River and closed highway 14 over Cameron Pass. Extreme heat and dry conditions and steady winds pushed the fire quickly through large areas of trees killed by pine bark beetles. The river and the road were the fire line until June 22nd when the fire crossed the road and burned through another 20000 acres in less than a day. That road (shown in green) was a critical link on the original route, used on both Day 1 and Day 4.

John Lee found a way around that but the day 4 reroute would have gone through Rocky Mountain National Park. The National Park Service requires permits for group rides in the park and that might have taken weeks. Next there was a fire in along the road from Laramie Wyoming to Walden Colorado that closed the Day 2 route. John found a way around that. Then it rained hard in Front Range and the Piedmont. The rain extinguished the fires at Cameron pass and in Wyoming so the roads reopened.

A day or so later a landslide closed Cameron Pass again. That's very common in the wake of major forest fires. The slide was cleared 2 days before the ride start. John decided to stick to the Day 1 and 2 reroutes and go to the original route on days 3 and 4 unless there was no alternative. Many thanks to John for his dedication and skill at finding options in that land of few roads. I was very concerned that the ride would be canceled in the final weeks and days leading up to it.

The rains also broke the heat and cleared the smoke out of the air. We had fantastic weather for the ride - no rain and not very hot by Colorado standards until the last day. I should say that the weather you saw on the road depended on how fast you were, as is often the case over 4 days and 750 miles.

This report documents my experience of the ride with some digressions on the history, geology, and environment of the beautiful country we rode through. I'm not a geologist, or a geographer, or a historian, or an environmental scientist. I'm just an interested amateur and I apologize for anything that I get wrong. Also, if you're not interested in all that stuff, feel free to skip over it. There is information about the actual ride buried in here somewhere, and lots of pictures. ;-)

The Rocky Mountains are at least the third mountain range to occupy what is now Colorado and Wyoming. Two mountain ranges have eroded to sea level or below leaving traces in the metamorphic rocks that formed beneath and the sediments that were deposited as they wore away. 140 million years ago the region was under a shallow sea that stretched across the continent from what is now the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. This sea was home to giant sharks and swimming dinosaurs.

Thousands of feet of sediment collected in the Western Interior Seaway and over time transformed into sedimentary rocks like sandstone and shale. The sea left the area about 70 million years ago when the Rocky Mountains started to rise up.

The mountain building was probably due to some change in the interaction between North America and the Pacific Ocean, like a piece of high priced coastal real estate being added on to California. The Rockies came up under the former western edge of the interior seaway. That's why there are sedimentary rocks on the highest parts of the Rocky Mountains.

During the Rocky Mountain buildup, rocks of different ages were bent and shuffled on top of each other. In many places older rocks ended up on top of younger rocks. Erosion wore down through the sediments and exposed the cores of the ancestral ancient mountains. That's why some of the exposed rocks are over 2.5 billion years old, half the age of the earth. Sedimentary rocks that were laid down in flat parallel layers were bent and tilted into new shapes. Molten rock from below intruded into the mix and broke through to form volcanoes, like the Rabbit Ears mountain range. What's left now a complex quilt of rocks of different ages and types. By 5 million years ago, everything was mostly buried in debris from erosion of the "new" Rocky Mountains.

Around 2 million years ago the land started rising again. As it rose, rivers started flowing faster to drain the uplands into the oceans to the east and west. As the rivers gained power they cut down through the thousands of feet of sediments to the hard rock core of the buried mountains. This continued as the mountains and plains rose another 5000 feet or more and the sediment fill eroded away. The rivers stayed in their original beds, regardless of what came up from below. The result is that now there are rivers that cut straight through ancient hard rock instead of going around, like the Colorado river through Byer's Canyon on Day 3.

Our ride took us from the high plains east of the Rockies, over the continental divide, and into the high valleys between the Front Range and the mountains to the west. The high basins were called "parks" by the early white settlers because of the relatively flat terrain, the abundant grasses, and the rivers flowing through them. The route took us through North Park and Middle Park in Colorado and beyond to the area around Steamboat Springs.

The ride started at 04:00 on June 9th. Day one took us through the Piedmont and foothills of the Front Range, across the northeast Corner of the Front Range into the Laramie Basin of Wyoming. From Laramie, we crossed the Snowy Range of the Medicine Bow Mountains and dropped into the South Platte River Basin.

One thing that made this ride difficult for me was that I started out too fast. I was riding in the lead group for far longer than I should have. I had a "rush of blood to the head" as the British say. I ended up paying the price later that day and in the days to follow. I knew better but it's hard to resist when you are feeling good at the start of a big ride. It was a perfectly reasonable pace for the group, I was just in the wrong group.

East of the Colorado Front Range there are many formations called hogbacks. These form when a series of sedimentary deposits are tilted up, as they did when the Rockies were formed. Sandstone layers are much harder than the shale and mudstone layers. The shale erodes away above and below the sandstone, leaving the edge of the sandstone projecting up over the eroding shale on west side of the hogback. They kind of look like ocean waves, smooth on the back, steep and broken on the front. The first foothill ridge you encounter when approaching the Rockies from the east is called the Dakota Hogback. It stretches about 700 miles from southern Montana down into New Mexico.

The first part of the ride went by fast. It was relatively flat. The morning was cool and overcast. I dropped off the fast group after about 40 miles. The first control was at Vern's in Laporte, about 65 miles from the start. By then I was starting to pay the price for going out too fast. I was still OK but feeling more tired than I would like with 150 mile to go to the Day 1 sleep stop. Vickie Tyer of the Lone Star Randonneurs was in good spirits though, as usual. Vickie has been on every 1200k ride I have ever done. Guess I should ask her which one we're doing in 2013.

Up to this point we were still in "civilization". There had been towns and ranches along the way and we had passed through parts of Loveland and Fort Collins. After Laporte, there was one store a few miles ahead called Ted's Place at the east end of the Cameron Pass road then there was 50 miles of wide open spaces to Laramie, Wyoming. I decided I would top off with water at Ted's Place so I left Vern's without filling my camel back. (Warning - do not try this at home.) There were at least 60 people at Ted's place, including tour buses, because the road over Cameron Pass was closed again due to another landslide. I went in but it would have taken at least half an hour to get close to the bathroom or the counter so I just continued on.

It started to look like rain on this stretch but it never materialized. We just had some mist and light rain. A couple of days before it was torrential so this was OK with me. Just like Seattle but warmer.

Soon we left the sandstone hills of the eastern slope and entered the Front Range of the Rockies. This area is made up of billion+ year old granite and metamorphic rocks.

I really started to feel the effects of starting too fast on the way up to Virginia Dale at around 80 miles. I was starting to get cramps in my calves so that I couldn't stand up on the pedals. I still had 130 miles to go that day including a 10000 foot pass. I was starting to think that I might not make it when my friend Noel Howes overtook me and asked how I was doing. I told him about the cramps and he gave me two electrolyte tablets to mix in my water bottle. That was a major help, before long the cramps were fading and I was making better progress, but still pretty slow. I was hesitant to stand for fear of triggering the cramps. I started to get some chaffing from the saddle which persisted through the rest of the ride.

Virginia Dale has the only stage coach station still standing in the nation. Unfortunately, the Cafe there is just as out of business as the stage coach line. I was worried that I would run out of water before Laramie since I hadn't topped off. One of the volunteers, Jim Kraychy, was there in the drop bag truck but he was out of water. I took some snacks and headed out.

I headed off from Virginia Dale in a troubled state of mind with 40 miles to go to Laramie. Mistakes had been made. But God is kind to fools and randos so I found an open rest stop with a water fountain and I was back in business.

During this stretch I had the pleasure of riding with Ken Bonner, one of the most indefatigable Randonneurs of our time. He has over 300,000 kilometer of randonneuring under his wheels and holds several ultradistance speed records. He once did half of a 600k, stopped and ran a marathon, then got back on his bike and finished the 600. This year he did three 1200k rides in 6 weeks. He is very a strong and fast rider so I don't see him very often but he is always friendly and interesting to talk to. We talked for a while which helped me stop obsessing about myself. I needed to focus on something other than how I felt and how far I had to go. Talking to Ken was just the ticket. We rode together until we reached the top of the climb. Then he was off like a shot, which I fully expected.

After we crossed the summit into Wyoming, we were about 10 miles west of a geologic formation known as "the gangplank". This is the one area where the vast blanket of debris that buried the Rocky Mountains up to their necks 5 million years ago did not erode. There's a continuous gentle grade all the way to the top of the Laramie Mountains. The Union Pacific Railroad has used this route since the 1860s and Interstate 80 has followed. From the Missouri River at Omaha, Nebraska to Cheyenne, Wyoming you climb 7500 feet in 500 miles on a steady 0.3% grade. Between Cheyenne and Laramie you climb 40 miles at 1.3% to the crest of the Laramie Mountains then drop down into the high range land of the central Rockies. It's the easiest way to get across the Rockies between Canada and New Mexico.

The town of Laramie is situated between the Laramie Range to the east and the Medicine Bow Mountains to the west. The rail line and the Interstate head northwest out of Laramie and skirt around the northern edge of the Medicine Bow Range. Our route went due west out of Laramie across the Snowy Range, part of the Medicine Bow Mountains.

We rode across plains to Laramie. I took a break in Laramie with Noel Howes and several other riders at the McDonald's. Say what you will, you always know what you are going to get at McDonald's and it will include plenty of salt.

Noel and I left together. It was about 25 miles from the Laramie to the base of the Snowy Range. After a while I started to notice a strange sort of writing on the shoulder of the road but I couldn't quite figure out what language it was. If this had been day four I'm sure I could have read the inscriptions.

Just before you enter the Centennial Valley there is a large mass of rock to the south called Sheep Mountain. It's another lump of 1.4 billion year old granite

The land south of the Snowy Range Road near Sheep Mountain is called the Big Hollow. It's a depression that was not caused by glacial carving or water erosion. It was caused by wind. During the last Ice Age, a steady wind blew down off of the mountain glaciers. The wind scoured out the glacial gravel and silt that was continually being eroded from the mountains. The whole area between Laramie and Sheep Mountain is covered with glacial gravel and silt except in the Big Hollow, where 500 feet of gravel was blown away to expose the 80 million year old limestone and shale underneath.

Centennial was the last stop for service before Riverside, 50 miles away on the far side of the Snowy Range. I was never sorry I had brought a camelback to carry extra water on this ride. They aren't very comfortable but running out of water is worse. Centennial is a town of 270 people 30 miles from Laramie. I was surprised to find they had public Wi-Fi. The cashier at the store told me that the weekend population is about 1000 when skiers, hikers, and motorcycle riders come around.

I had a bit of a struggle after Centennial. The road climbed steadily for 12 miles. The elevation gain was about 2800 feet, not that bad really. But it was 150 miles into the day and the climb topped out at over 10,700 feet. Plus it was hot and dry for a Pacific Northwest boy like me. I had to stop 5 or 6 times on the way up to get my heart rate down to a reasonable level. It took me two and a half hours to do the 12 miles to the top of the pass.

And you may ask yourself, well, how did I get here?

The top of the range was about 4 miles of rolling hills. It's not called Snowy because it gets a lot of snow, though it does. The name comes from the white quartzite at the crest of the range that makes it look like it has snow on it all year round.

This bridge is on the outfall stream from Lake Marie about 2 miles past the summit. I had to include it because I actually turned around and went back to get the picture. I wouldn't want to waste the extra pedal strokes. 95% of my pictures are taken while rolling.

After the east summit, the next 25 miles were quite nice. Almost 4000 feet of descending. I started to feel much better after an hour of going fast without pedaling. It was about 6:30 PM when I left the National Forest and entered range land.

This hill is made up of 3 billion year old rock. That's old even by geologic standards, more than half the age of the earth. It has been bent, folded, spindled, and mutilated, buried, cooked, eroded, and exposed for the equivalent of one hundred million human generations. This is known as crystalline basement rock. It's the stuff that the cores of the continents are made of. But that day I was a lot more interested in the shade of the trees growing on it.

The descent ended at a T intersection. Saratoga, the overnight stop, was 7 miles north. Due to the reroute we had to turn south to make the distance come out right. We had to go 10 miles south to Riverside and then 17 miles back to Saratoga. This is one of those cases where you might ask yourself "Why am I doing this?". This time it was well worth the effort. As I headed south, a large thunderhead was forming over the Medicine Bow Range. The sky was otherwise perfectly clear.

The sun was setting to the west with a slow fading red glow.

I got to Riverside a couple of minutes past 8:00 and the store had just closed. I had to go into the Mangy Moose Saloon to get

my card signed. The bartender and patrons were friendly and asked me questions about the ride as I got my card signed

and bottles filled. I left and headed north toward Saratoga. It was getting darker. The storm to the east was pulsing with

lightning inside the clouds. Stars slowly appeared between the sunset glow and the flashing storm. There was no wind and all was

quiet except the sound of rolling tires. A pool of light from my headlamp illuminated the road ahead. A meteor shot across the sky

above the storm. I thought: "This is why I came here." How else would I ever come be in that place at that time with the time

and space to really see it?

I didn't take a picture but the moment was etched in my memory so I made a sort of composite replica of it with Photoshop.

After that I totally forgot about being late or tired. I felt charged with energy. I did the last 8 miles to Saratoga, which was flat, at an average speed of 19 mph. I got into the overnight, at the Hacienda Motel, at 21:15. The control workers put out a lot of good food and drink. The rooms were nice and clean and I had time for a shower. I got about 4 and a half hours of sleep.

Sometime during the day I had dropped my camera and broken the LCD. I couldn't see what mode it was in so I set it up by memory from the noises it makes in different modes. I really wasn't sure if it was working at all but it was making shutter sounds so I decided to assume that it was working and continue using it. At the end of the ride I found that it had worked the whole time and the pictures in this report were intact.

On Day 2 I started out riding with fellow Seattle Randonneur Noel Howes, which I should have done on the first day to avoid the early burnout. We left Saratoga at 2:45 in the morning and rode back to Riverside before heading south through the high plains toward the Colorado border. It was a nice day for a ride and the landscape was beautiful in a particular sparse way that I like.

We were climbing along the North Platte River drainage. The terrain was rolling and generally rising for the first 100 miles to the base of the major climb of the day, at Rabbit Ears Pass

We stopped at the Colorado border for a photo op. A stranger drove up to take some pictures of his own and we got to talking. I don't remember where he lives but he told us that he travels to New York every year to do the Five Boroughs bike ride. That's one I'd love to do.

Over the next 50 miles we traversed North Park from north to south. North Park is bounded on 3 sides by mountain ranges: Park Range to the east, Rabbit Ears Range to the south, Never Summer Mountains and the Medicine Bow Mountains to the west. This place is pretty empty, the total population density is less than 1 person per square mile. The roads are empty too. You can go a long way without seeing a soul.

At 100k we stopped briefly at the Walden control, in the big (and only) town in North Park - population 732. We would stay the night there 37 hours and 300 miles later. From Walden, Noel and I headed southwest toward Muddy Pass in the gap between the Rabbit Ears Range and the Park Range.

Strangely enough, Rabbit Ears Peak and Rabbit Ears Pass are not in the Rabbit Ears Mountain Range, they are in the Park Range, but the same volcanic events that created the range created the peak. The "Rabbit Ears" are weathered remnants of lava and ash that flowed from volcanoes to the east over the ancient rocks of the Park range.

North Park trends steadily higher toward the south. By the time you reach the foot of Muddy Pass you are within 200 feet of the pass summit at the junction of Highway 40 and Highway 125. It may not seem like much of a pass but rainfall on the north side of the road takes a 3000 mile journey to the Gulf of Mexico via Grizzly Creek, the North Platte, the Platte, the Missouri, and the Mississippi. Rainfall on the south side of the road takes a 1300 mile journey to the Gulf of California via Muddy Creek and the Colorado River.

We were at about 100 miles on the day when we got to Muddy Pass. The weather was hot and we had 30 miles to go to the

next town at Steamboat Springs. While I was waiting for Noel and pondering where we would find the next water a guy pulled up in

his car and said: "You OK? You need anything?" I said: "Do you have any water you can spare?". He had a full gallon jug that he

kindly shared with us to top off our supply. Alas, I don't remember his name but he told us he had ridden his bike over Rabbit

Ears Pass many times and he just wanted to help us out. Thank you, whoever you are!

When we got to the pass, there was a guy on a motorcycle having his picture taken. He was saying "I got here under my own power"

until he noticed us on our bicycles and added "with some help from Firestone and Chevron and BMW" with kind of a sheepish grin.

The east and west summits of the pass were separated by 7 miles of rollers that added about 500 feet of up and down through a mixture of pine forest and open grassland. The Yampa River valley to the west is much lower than North Park. There's a 2500 foot drop over 7 miles on the west side of the pass. There are a series of signs on the road to indicate that they are not kidding about the descent.

As I got down toward the bottom of the slope I noticed that the wind was not cooling me down any more, even at 40 mph. It was like riding into an oven. There was probably a 25 degree temperature difference from the top to the bottom of the pass. I would guess that it was in the mid 90's at the valley floor.

Noel was somewhat more cautious than me on the descent so I was ahead of him rolling into Steamboat Springs. I felt the need to get some more electrolyte supplements so I stopped into Steamboat Ski and Bike Kare. Noel arrived at the bike shop at about 2:30. Because of the fire induced reroutes there was a 75 mile loop added out of Steamboat to make the distance work out. This was the one part of the ride that had not been pre-ridden. We had the following conversation with a young Australian woman working at the bikeshop:

"Where did you come from?"

"Saratoga, Wyoming"

"How far is that?"

"About 125 miles, over Rabbit Ears"

"Huh...where you headed now?"

"We're going down the main road to Hayden then over to Oak Creek and back to Steamboat"

"Oh, don't go that way to Hayden - nobody goes that way, there are much better ways to get there."

"Well, that's the course, we have to go that way."

"That doesn't make any sense"

"I know"

"Then where? To Oak Creek?"

"Yes, Oak Creek"

"Past the coal mine?"

"I don't know, is there a coal mine?"

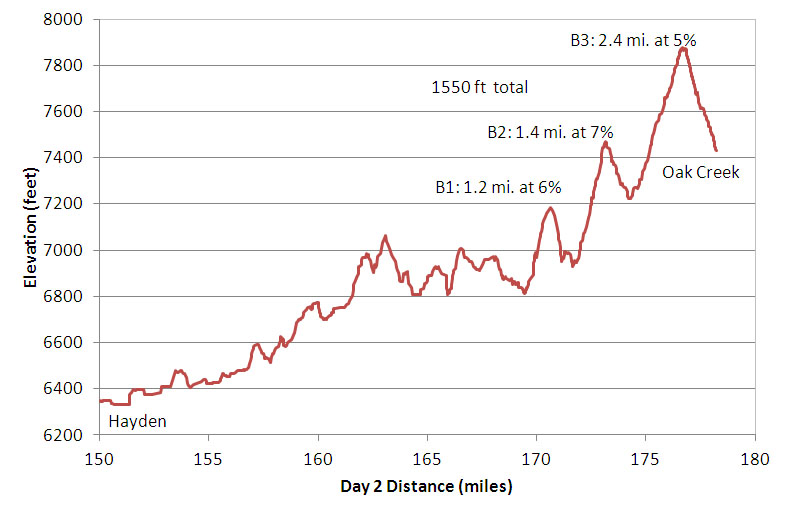

"That's the Bitches, you're doing the Bitches!"

"Who are the Bitches?"

"We call that road the Three Bitches because of the hills you climb to get over to Oak Creek. That's one of our hard training routes."

"That sounds exactly right"

"So you're doing this 75 mile loop starting now and coming back here?"

"Yep, we're staying in Steamboat tonight"

"That's crazy"

"I know"

After restocking and having a quick meal we set out for Hayden at 3 in the afternoon. Our first adventure was on the 25 mile trip to Hayden on US40. The first 15 miles were not great, plenty of traffic but OK. After that it got interesting. This picture is from Google Street View. I was not crazy enough to take pictures on that stretch.

We were going in the same direction as the truck in this picture so it was a white knuckle ride between the rock face and traffic.

There was also fallen rock and debris on the "shoulder", if you can call it that. The other side of the road was a steep drop

to the Yampa River. We were relieved to exit the cliffs after about 5 miles of high stress.

The road continued another 5 miles or so to the town of Hayden. We passed the turn off to Oak Creek to get to Hayden so we would

have to return on highway 40 for 3 or 4 miles after the control. Noel and I knew that Hayden might be our last chance for supplies

before getting back to Steamboat Springs so we topped off the water and bought some food for the remaining 50 miles of the day.

We headed back toward the road to Oak Creek.

About a mile out of town Noel stopped because he thought one of his tires was leaking but he wasn't sure. He stopped a couple of

times to look at it and then decided to patch the tire. I was waiting but he could tell I was kind of fidgeting to move on so he

told me not to wait. I went on but I really felt bad about it later. After fixing his tire, Noel missed the turn to Oak Creek

and started back up through the gauntlet toward Steamboat Springs. He lost about an hour, which can be a big deal on a 1200k.

I feel like I could have prevented that if I had stayed with him. I find it to be a vexing question whether or not to stay with

someone who is delayed. Sometimes I do, sometimes I don't. It depends on a lot of things like what the problem is, how tired

I feel, how close we are to the cutoff, if other riders are around, what I know about their capabilities, etc. Everyone on

these rides should be self sufficient but that doesn't mean you shouldn't help people out. I don't have a good answer on how

to draw the line.

The road climbed steadily from the turnoff at US40. The Twentymile Coal mine is one of the most productive mines in the world, producing 9 or 10 million tons of coal per year. Fortunately they don't truck it out, there is a dedicated rail line to the coal mine. It's low sulfur coal used in power generation plants. Think on that next time you plug in your electric car. The power has to come from somewhere.

The mine belongs to Peabody Coal Company, which reminded me of a song from long ago:

Oh daddy won't you take me back to Muhlenburg CountyParadise, Muhlenburg County by John Prine

Down by the Green River where paradise lay?

I'm sorry my son but you're too late in askin'

Mister Peabody's coal train has hauled it away.

The coal beds are layered with sandstone and shale that was deposited in the Interior Seaway 75 million years ago.

Before the coal mine I was thinking that one or more of the hills I had climbed were big enough to count as part of the Three Bitches. Wishful thinking. After the coal mine we reached the bottom of the first real climb. They were not the worst hills in the world but I was at 170 miles on the day and almost 400 miles from the start the day before. But what are you going to do? The destination was on the other side of the hill. I have found that somehow you always end up at the top of the hill so there's really no use agonizing about it. Not that I'm always able to follow that guidance myself.

Hill pictures are usually disappointing because they never look as bad as they feel. You can't see the altitude unless you know where exactly up is. Suffice it to say it took me 1:10 to go 7 miles from the coal mine to the top.

It was near dark when I reached the top. I had a reasonably close encounter with a deer right at the crest of the hill. That made me cautious but I was still looking forward to the 1300 foot drop over 20 miles between me and the hotel in Steamboat. But the adventures were not over yet...

After a fast descent as night fell, I reached the control town at Oak Creek. This was a timed control which meant I had to get a signature from some "establishment" in town to prove I was there within the time limits. I arrived at 5 minutes after 8 by which time the sidewalks had been rolled up and stowed for the night. There was nothing at all open on the main street. I looked across Oak Creek and saw one light still on - at the OC Ink Drilling Tattoo Parlor. I thought "what the hell" and then headed over for a signature. Three highly decorated guys were in there. The artist was hard at work with a customer. The sweet sounds of metal music filled the air. I explained that I was on a kind of rally ride where I had to get signatures from people at certain places to prove I did it. They said "cool". The tattoo artist set down his instrument and signed my card and I was on my way. I know I should have asked him to tattoo the signature on my arm but he was busy and I was kind of in a hurry at that point.

It was full dark by the time I left Oak Creek. I still had 17 miles to go to the overnight but it was 900 feet lower so no problem, right? An hour maybe? A little while later I saw a sign that said "Pavement Ends". I had to laugh at the point. Sure, why not. I love riding gravel downhill in the pitch dark. The pavement had been completely torn up for about a mile. It was just coarse gravel and ruts and dust. I passed another rider walking his bike who was just seething about the road condition. Every time a car came I pulled over and stopped to waited for them to pass. I can only imagine what they must have thought about seeing bikes out there at night. After that it was clear sailing. I arrived at Steamboat Springs at 9:40 PM, about 19 hours after I left Saratoga. There were 5 riders left out on the road when I arrived.

The control at Steamboat Springs closed at 2:29 AM on the 11th. Normally I would have left at least an hour before closing to hold on to some margin for mechanical or physical problems before the next control point. This time I decided that I really needed to sleep or I would not make it through another day. I slept 4 and a half hours and left about an hour and a half past the official closing time. One thing that made the decision easier was that the timing for rides over 600k changes in the middle. The required average speed goes down from 15 kph to 11.4 kph (9.3 to 7.0 mph) after 600km. I was sure I could at least do 9 mph, especially with some extra sleep. This was a make or break point. I decided that if I could make the 70 miles to Kremmling before it closed 12:20 I would make it to the finish in time. If not, I was probably going to abandon. There was still one rider left at Steamboat when I rolled out but I found out later that he abandoned at Steamboat so I was the last one on the road.

I was now following the Yampa River. After about 30 miles I reached Finger Rock. Finger Rock is a 10 million year old volcanic pillar formed when the magma feeding a volcano cooled and solidified. The mountain is gone but the core remains.

That's the theory anyway. Maybe it's just one of these gentlemen buried up to the hand:

It was a fine morning for riding, cool but not freezing, clear skies, light wind. I enjoyed riding through the dawn and early morning hours. With a few exceptions, the course climbed continuously for the first 50 miles. There was almost no traffic on the road until I got near Tonopas at about 07:00. There the course turned onto Highway 134 toward Gore Pass.

The Gore Range is named after a famous schmuck, Sir Saint George Gore, Baronet of Manor Gore in northwest Ireland. This "sportsman" was an absentee land owner who received about $200000 a year just for breathing. Being rich and bored, he decided it would be entertaining to take a hunting vacation in America from 1854 to 1856. During that time he is said to have killed 100 bears, 1600 elk and deer, and 2000 buffalo. I don't care who you are, that's just nasty. Fortunately for all of us, he had no offspring.

It was another clear and beautiful day on the climb over Gore Pass. The temperature started to rise on the climb up Gore Pass but it still nice when I got to the top at about 9:20 in the morning.

After the pass there was a 17 mile descent into Middle Park. There were more Dakota sandstone hogbacks here on the west side of the Front range, just like the ones at Fort Collins.

I had to stay alert because the road was not empty. This deer crossed the road in front of me about 10 minutes into the descent.

At the bottom of the pass was the kind of view that can make you very happy or very sad depending on your state of mind. You know that you are going down that road to the farthest ridge you can see and that can be a source of anticipation or dread. This was a happy view because I was sure I was going to make it to Kremmling on time. The rest of the way to the control I spent speculating on what exactly a kremmling would look like if I saw one.

I was very happy to find that there were about 10 riders still at the control in Kremmling, including Noel Howes. I really felt that I would make it to the finish in time at that point and the feeling pretty much carried through the rest of the ride. That's when Noel told me about his navigation troubles the night before. I decided that we should stick together from then on because we get along well and besides we seemed to be having more trouble apart than we did when we were together.

So Noel and I headed east on Highway 40 toward Granby at about 11:00 AM. We were now heading upstream along the Colorado River.

After about an hour Noel had another flat. He had a lot of tire problems on this ride. I couldn't offer much material help because he had 650b wheels and I have 700c wheels. 650b tires are scarce as hen's teeth out there.

At mile 85 we reached an interesting place called Byer's Canyon. This is where the Colorado river cut down through thousands of feet of sediment to form a gorge in billion and a half year old metamorphic rocks.

Byer's Canyon is named after William Newton Byers, founder of the Rocky Mountain News. He bought the entire town of Hot Sulfur Springs at the east end of the Canyon in 1864 so he could build a resort at the hot springs.

We continued on along the Colorado toward the appropriately named Windy Gap. The road climbed above the river and past a rock face at the narrowest part of the gap. We had strong headwinds there. It was getting hotter and windier and we could see dark clouds forming ahead.

Noel came up with a novel idea when the road dropped back down to the river. He didn't say much and it took me a while to figure out what he was doing. He went for a dip in the Colorado right there in Windy Gap. I was too chicken to do it myself because I was still having butt problems and I was afraid that getting my shorts wet in the river would make it worse. I just went wading but it sure felt good to get off the bike and cool off a little.

After a mile or so we passed the turnoff to Willow Creek Pass. The course did a 33 mile out and back up to Grand Lake at the west end of Rocky Mountain National Park. We started to see a lot of the other riders headed back toward Windy Gap. They were all smiles with the nice tailwind pushing them along. When that happens it's best not to calculate how far ahead of you those riders are. We could see that there was a big thunderstorm going on over Grand Lake and the wind was blowing straight down the hill from our destination.

During the pre-ride scramble to find open roads, one of the potential routes went past Grand Lake and through Rocky Mountain National Park. At the time I thought "Cool, we get to ride on the highest paved road in the country - that will be great." John Lee Ellis had said that it was not a good choice, independent of the issue with park permits. I soon understood why. This is a heavily used road because it is the most direct route over the mountains from Denver and it goes through a very scenic and popular national park. It was not so pleasant after all of the lonesome roads we had been on up to that point. With that and the headwind, Noel and I found this stretch kind of aggravating.

The clouds over the lake looked threatening but they never crossed over to our side and the wind stopped as we approached Grand Lake.

Our control was in the town of Grand Lake. When we got there I thought to myself: "I just got up at 3 in the morning and rode 100 miles to buy a candy bar at a gas station." Rando life. We were just over 500 miles into the ride at that point.

Like many of the roads we ride, this road is very popular with the other kind of bikers. This beautifully restored Indian was a prime example.

While we were at Grand Lake the skies cleared to the west, which was nice, but the wind turned around so that we got headwinds both ways. That might have affected our opinion of the road from Granby to Grand Lake. The faster riders had a ripping tailwind on the way back to Granby. Still, it was a nice day for a ride.

Noel and I joined up with three other riders heading out of Granby: Art Fuoco and Rorie Anderson from Florida and Vickie Tyer from Texas. As we turned off Highway 40 toward Willow Creek Pass the wind dropped to nothing. The first bit was a 600 foot climb away from the Colorado River along Coyote Creek. It was 5:30 in the afternoon and very still. There was no shade on the road so it got very hot on the climb.

After the initial climb the sun dropped behind the ridge and for about 10 miles we followed the Willow Creek as it wound back and forth across a peaceful valley. The heat let up and it was a very pleasant ride.

Art Fuoco and Rorie Anderson are from Central Florida. We had played leapfrog on the ride from Hayden to Oak Creek the day before. I had met Art at the 2010 Cascade 1200. He has done the Cascade twice and PBP twice, once with a broken wrist! Art is a very strong and determined rider. Rorie is an avid cyclist who came over to the dark side (randonneuring) in 2010. She was on her first 1200k. They rode well, at least it looked that way to me. I still can't figure out how you train for a ride like this in Central Florida, where the freeway overpass is considered a major climb.

There were some interesting rock formations on the upper part of the climb. 2 miles east of Willow Pass is an 11000 foot volcanic peak called Radial Mountain. Vertical rock slabs called dikes shoot off in many directions from the summit of Radial Mountain. They were formed underground about 25 million years ago when molten rock was forced through along cracks and faults in the pre-existing shale and sandstone. The softer sedimentary rocks have weathered away and the dike is left standing like a stone wall. This one is maybe 10 feet wide and 3 miles long. Most of the dike is still buried in 40 million year old sedimentary rocks from the Interior Seaway.

At about 7:30 PM we reached Willow Creek Pass. Willow Creek Pass is between North Park and Middle Park and between the Rabbit Ears Range to the west and the ominously named Never Summer Mountains to the east. We were at 150 miles on the day. We still had daylight and I was feeling pretty good about being there before dark.

We had 32 miles and 1500 feet of descending to go to the overnight back at Walden. Piece of cake, right?.

But again, the day's adventures were not over yet. It was great for the first 10 miles or so down to the Illinois River. Long enough to convince ourselves that we were home free. Then we caught another headwind. It wasn't really strong but it was constant and took our speed on the flats from about 12 mph down to about 9. By then it was full dark, really dark. Few stars due to the broken overcast. We rode along in the tunnel of light from our headlamps. Outside of that you could see ranch house lights from miles across the flats. The ranch lights were so far away that you couldn't detect any change in the bearing to the light. Cars would come up over the low rollers ahead and you could see them coming for long minutes before they passed. It was like riding on a chip seal treadmill. This special treat was reserved for only the last half dozen riders. The rest reached the overnight before the wind changed. C'est la vie. It's worth mentioning that I had the opposite experience at Paris-Brest-Paris 2011. I missed all of the foul weather while the fast riders got hammered with hard rain and thunderstorms. You just never know.

Noel and I rolled into Walden at 11:05 PM, five minutes after Rorie, Art, and Vickie. 180 miles in 18 hours that day.

The difference between a 1000 kilometer ride and a 1200 is Day 4. Convincing yourself that getting back on the bike that fourth morning can be difficult but by then you have so much blood, sweat, and tears invested that you absolutely have to do it. Now when I do a 1000k I appreciate the day after even more because I'm not riding!

We rolled out of the Walden Control at 5:30 AM, an hour and a half after the official closing time. I got in about 4 and a half hours of sleep. The last rider before our group had left more than an hour earlier. Our group consisted of me and Noel from Seattle, Vickie Tyer from Texas, and Mordecai Silver from New York City. It was 150 miles to the finish and we had until 10:00 PM so we only needed to do 9 mph in total. The tricky part was that the first control at Rustic was 57 miles away and we had to be there in 5 hours and 50 minutes, an average of about 9.8 mph. The first half was a 2500 foot climb to 10,276 feet. The second half was a 3400 foot descent. It was a calculated risk. In retrospect we could have left a little more margin for mechanical breakdowns, etc., but I felt at the time that going with less sleep was a bigger risk. In the end, we averaged 9 mph going up and 19 mph going down so we had plenty of time.

Our gang of 4 started out on the one remaining road out of Walden that we hadn't taken yet. This one crosses the Front Range at Cameron Pass and drops down to Ted's Place and Fort Collins. It was a spectacularly beautiful day for the last big push.

The first 25 miles was a very gradual climb along the Michigan River. That took us up to 9300 feet. After that we had a 4% grade for 4 miles to the top of the pass.

The 12,458 foot Nokhu Crags southwest of the pass is made up of sediments from the Cretaceous inland sea that were cooked, bent vertical, and faulted upwards during creation of the Never Summer Range. You can see a lot of trees in the foreground that have been killed by Pine Bark Beetles

A lot of people believe that the pine bark beetle kill is causing more severe forest fires but that may not be true. University of Wisconsin forest ecologists Monica Turner and Phil Townsend did a study using NASA LANDSAT data and observations on the ground that showed the beetle killed trees are not especially favorable to fires. When they compared where fires spread to where the dead trees are they don't match. On live trees, the small branches and needles are full of volatile chemicals. Dead trees don't produce the kindling needed to start the logs on fire. There is some evidence that fires actually slow down when they reach stands of beetle killed trees.

Pine beetles are native to the western forests but most of them normally die off due to sustained cold in the winter. That hasn't been happening in recent years so the beetles have spread through large areas of the Rocky Mountains.

At 07:45 we arrived at the pass. As you can tell from this picture of Noel, were all pretty happy to get there because it was the last major climb before the finish.

We averaged 24 mph for the next half hour. It was very very nice to be there. I heard later that the early risers had frozen their butts on the descent but it was gorgeous when we got there. Naturally, we paid for it later...

We arrived at the control, Glen Echo Resort in Rustic, at 09:20. We were there 2 hours before the control closing time. At that point we were 90 miles from the finish and we had 12 hours and 40 minutes to do it. We took an hour break for a real meal. If I recall correctly I had a lot of iced tea, a Denver omelet, bacon, hashbrowns, and a large vanilla milkshake.

State Highway 14 follows the Cache la Poudre River east of the pass. The name of the river means "Hide the powder" in French. In the 1820's some French trappers were caught by a snowstorm and forced to bury part of their gunpowder along the banks of the river. It is locally known as "the Pooder". This would have been a bad year to hide gunpowder in the canyon.

Soon after we left Rustic we reached the western limit of the High Park fire. On the higher ridges south of the river all of the trees were black and the ground was scorched by the fire. The road over Cameron Pass was closed for almost 3 weeks due to the Fire. It reopened 8 days before our ride started. A total of 259 homes were destroyed in the fire, making it the most destructive fire on record in Colorado. That record lasted about a week until the Waldo Canyon fire burned 349 homes near Colorado Springs.

For the next 5 miles the fire was contained south of the river. Everything north of the river was intact but almost all of the trees south of the river were burned. This campground at Dutch Gorge was opened when we went past.

About 7 miles from the control we entered a narrow winding canyon where the river had cut down through billion and a half year old granite and metamorphic rocks. The temperature was rising fast. I started to think what it must have been like for the firefighters walking into that canyon to try and keep the fire from crossing the river. Near Sheep Mountain the fire jumped the river and raced away to the north. It must have been hellish.

The following pictures show what it was like during the fire and what it was like when we were there. The fire pictures were taken by the National Guard soldiers and others who were on the fireline. When you think about what it takes to walk into that canyon to fight the fire it puts our bike riding exploits in perspecive.

As we went farther into the canyon we ran into a strong headwind. This is known as an anabatic wind. The sun heats the higher elevations faster because there is less atmosphere to insulate the ground from the sun. The warm air starts to rise and the cooler air from lower altitudes blows up the valley to take its place. In this case the air was accelerated by passing through the narrow canyon. Pretty soon we were working hard to maintain 13 mph downhill and the temperature was 103 degrees according to Noel's Garmin. It was like riding into an open furnace. This was worse than the descent to Steamboat Springs. This was our payback for not freezing in the early morning hours like the fast folks did.

After about 10 miles of that we needed a break. We came up on the Mishawaka Inn, a bar, store and concert venue about 10 miles from the bottom of the canyon. They were not really open but when we rolled up they let us in to buy snacks and drinks and fill our water bottles.

We got to talking about the High Park fire. The owners of the Inn were at home trying to decide what to do and they heard a sound that they thought was aircraft flying over head to drop water on the fire. It was the sound of the fire coming down the ridge toward their place. It looked hopeless. They made the tough decision to evacuate. After they left, firefighters (including many of their neighbors) saved everything except one house on the south side of the road. Now the fire is gone but the scars are still there on the surrounding hills.

We were there for about 20 minutes and felt better after the cool down. At high noon we headed out for the bottom of the canyon. Pretty soon we came across a group that had a much better plan for getting out of the canyon than we did.

We finally escaped the canyon at 12:30. It was, I think, the most interesting part of the ride. John Lee was right about this being the right way to go. I would not have missed it.

When we left the canyon the headwind let up but it was still hot. Once we reached Highway 287 at Ted's Place we had closed the loop that we started 75 hours earlier on the way to Laramie. The rest of the way back to the finish was similar to the first part of Day 1 but a little more direct. This time there was no risk that I would go out too fast. The next control was back at Vern's in Laporte. When we got there we had 2 hours and 40 minutes in the bank. We stayed about a half hour stocking up and then headed for the barn. There was a major paving project on the road in front of Vern's, as if it wasn't hot enough already. The asphalt was a little mushy in spots and the smell was pungent.

After Vern's we had 56 miles to go and 8 and a half hours to do it. It was hot and there was not much wind. We could see clouds but they were not close enough to do any good. There were many miles on long straight roads over rolling hills.

I think some Ayn Rand fans live here.

Our last supply stop before the finish was at Mary's Market and Deli in the town of Hygiene. It's a very nice and bike friendly shop with fresh cookies and pie and other delicacies.

The town of Hygiene is named after a sanitarium for tuberculosis that was built there in the 1880s.

Despite the heat we were having a great time laughing and telling tales on the last leg of the ride. We managed to unite Texas, New York City, and Seattle. We did our part for World Peace.

We still had a little more adventure left. At quarter to six we had 7 miles to go to the finish. We came upon a guy walking his carbon fiber road bike along the side of the road. We asked him if he needed any help. Damned if he didn't say yes! He had a flat and had already used his spare tube and his CO2 cartridge. We gave him a tube and loaned him a pump. Judging by how he was trying to put the tube and tire on with a lever I can guess what killed his spare tube. It looked like he didn't have much practice at that. While we did it for him, he asked if we were on a training ride. "Yeah, we are doing a big loop out of Louisville". Someone suggested he should bring a pump and he said (I am not making this up): "Every gram counts". Which is certainly true, especially when you're walking your bike for miles because you can't fix a flat. Anyway, after 10 minutes we got him on the road again and headed off toward Louisville.

So about 20 minutes later we were all rolling along laughing and talking about our roadside rescue when Noel slowed down and pulled over. He had yet another flat and this time the tube was sticking out of a hole worn through the tire. His tires were 650b x 38mm size Pari-Moto "event tires". Noel used these same tires on Paris-Brest-Paris 2011 and had stored them ever since. According to Compass Bicycles: "When you want the fastest 650B tire available today, the Pari-Moto is your choice. Superlight, with a thin tread, the Pari-Moto is designed for performance above all." Which is important, especially when you're walking, etc, etc. (Just kidding). We have now proven that they're good for one 1200k, but not for two. After 13 minutes, we patched the tube and booted the tire well enough to make the last 5 miles to the finish.

We rolled into Louisville just before 7:00 PM. The Lantern Rouge group finished at 7:55 PM. Our time was 87 hours and 55 minutes. It was an immensely satisfying ride. Every day was different but the best day was the last because of the great companionship in our little group. After Rustic we were not under any time pressure so we just rode and talked. All four of us had a great time, despite difficult stretches due to the wind and the heat. Couldn't ask for better ride partners.

Why do we do this? I have wondered that many times, especially on days 3 and 4 of big rides. I'm not a spiritual person but for me there is something about this kind of travel that links back to how people interacted with the world for all but the last one tenth of one percent of human history. It's easy to forget how big and how old the world is and how little and young we are as a species. For me it's sort of a secular pilgrimage. Out there you have room to think. It's like an extended meditation interspersed with suffering, which once would have been called a quest. It's humbling in a good way. In the face of the wide world it's hard to take yourself too seriously.

I would like to thank John Lee Ellis and the outstanding support workers for making this ride possible.

This report is dedicated to my randonneuring mentor, the late Donald Boothby. You made the world a better place.

If you enjoyed this report, you might like:

Paris-Brest-Paris

Cascade 1200

Wenatchee 600

or maybe not.